aku mihi nui e te whānau

tēnā koutou katoa

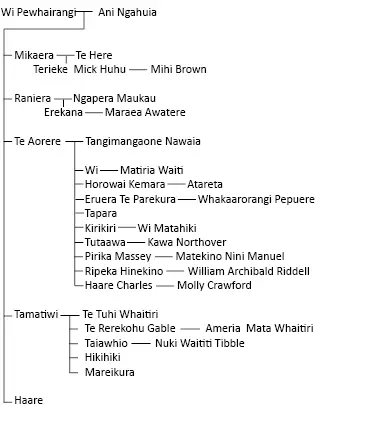

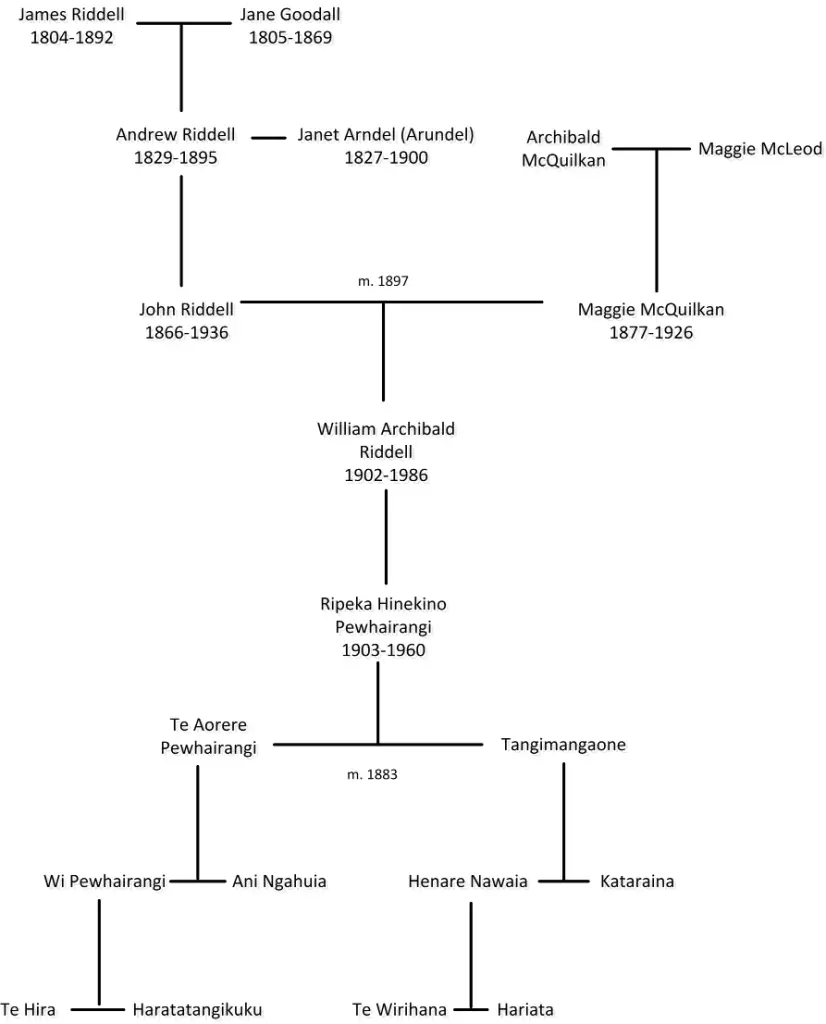

Riddell Whakapapa

The following has been written by my Uncle “Te Aorere (Awi) Riddell” for the purpose of our Family Reunion that was held in April 2012 at Iritekura Marae in Waipiro Bay.

These are his words, and I want to honour them by sharing it with the wider community

so anyone who is searching for their whakapapa, or background to where they have come from, can use this as a starting point for their own whakapapa journey.

Mihi

Papa te whaititiri, hikohiko te uira

I kanapu ki te rangi, whetu ki raro ra

Ru ana te whenua e

Tena tatou e te whanau; tena tatou nga uri o o tatou matua tipuna kua riro atu ki tua o te aarai. E tika ana me mihi atu, me tangi atu ki a ratou ma; na reira koutou te hunga kua moe, moe mai ra i o koutou moenga roa.

E mihi kau atu ana ki a koutou o te wa kainga, koutou te ahi ka e pupuri nei i te mauri me te mana o o tatou nei marae.

Ko tatou enei nga uri whakaheke o o tatou tipuna maatua me o tatou hoa rangatira kua eke nei ki tenei to tatou nei marae ki te whakanui i te kaupapa whakahuinga ano o te whanau. Na reira nau mai, haere mai; haere mai ki te whakahoahoa, ki te ako, ki te whakamohio i tenei mea te whanaungatanga, ki te katakata, ki te waiata, kia mohio ai tatou ki o tatou whakapapa.

Ko te tumanako, kia pai to tatou noho. Hei te mutunga o to tatou hui, kia hoki atu tatou ki o tatou kainga i runga i te hari koa o te ngakau, me o tatou kete kikii ana i nga korero e pa ana ki to tatou whanau.

Kia ora tatou.

Introduction

Family reunions are times of celebration; times when we can get together to find out about ourselves, our forebears, who they were, what they did, where they were from.

Time does not permit us going into too much detail about the past; so what I have attempted to record here is but a “scratching of the surface” of the stories of our ancestors. As well as a look at the past, we should also look at where we are now as a family, and perhaps look to the future to try to foresee what that might hold for us.

The Riddell family is a very big family scattered throughout the country and around the world.

This presentation merely covers those who descend from William Archibald (Bill or Billy) Riddell and his first wife, Ripeka Hinekino Riddell (nee Pewhairangi) and those of his second wife, Tahua Gomez (nee Honetana).

I have attempted to give a brief outline of our whakapapa Maori and our whakapapa on our Scottish side, and then the joining together of the two sides.

Our Māori whakapapa

Hei Timatanga Korero

Let us begin this journey by looking back at where we come from and from whom we are descended. The study of one’s whakapapa (genealogy) can be a fascinating and absorbing exercise.

“Ko Hikurangi te maunga, ko Waiapu te awa, ko Ngati Porou te iwi”

(Hikurangi is the mountain, Waiapu is the river and Ngati Porou is the tribe).

WAKA: Horouta

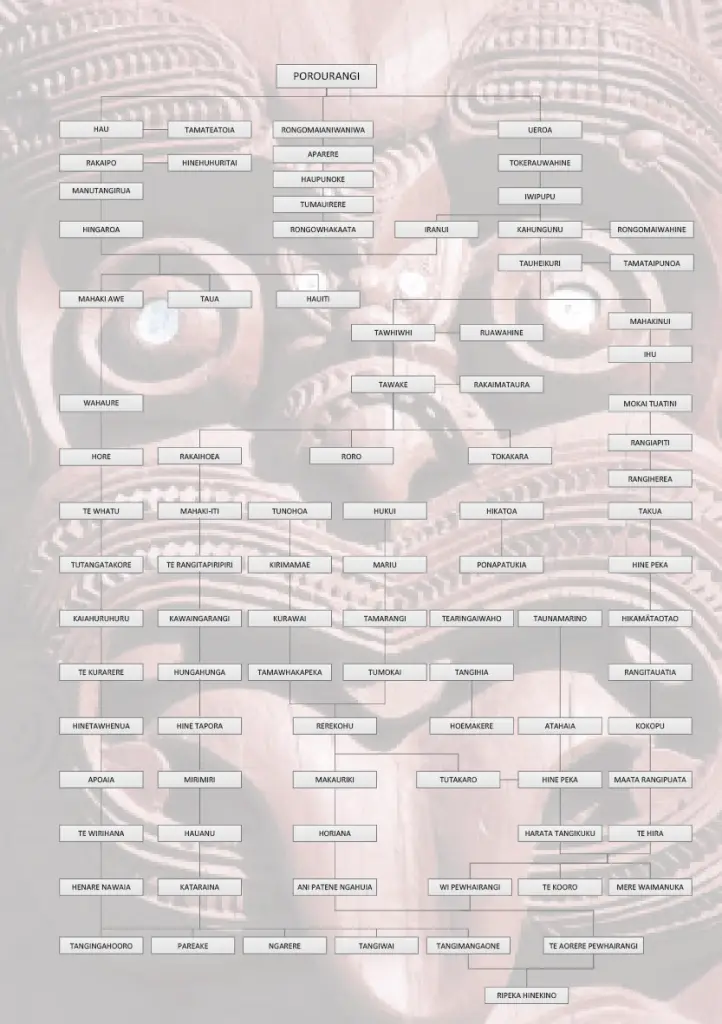

IWI: Ngati Porou (Eponymous ancestor: POROURANGI)

BOUNDARIES: “Mai i Potiki-rua ki Te Toka-a-Taiau”. (From Potiki-rua (near Lotten Point) to Te Toka-a-Taiau (a rock in the Gisborne Harbour which was blown up by the Harbour Board to make the shipping lane deeper)

OUR HAPU: Te Whanau-a-Ruataupare (Tokomaru Bay) and Te Whanau-a-Iritekura (Waipiro Bay)

OUR MARAE:

- Tokomaru Bay:

Pakirikiri Marae;

Wharenui: Te Hono-ki-Rarotonga;

Wharekai: Matikotai,

Waiparapara Marae; - Waipiro Bay:

Iritekura Marae;

Wharenui: Iritekura;

Wharekai: Tangimangaone;

Taharora Marae;

Te Kiekie Marae.

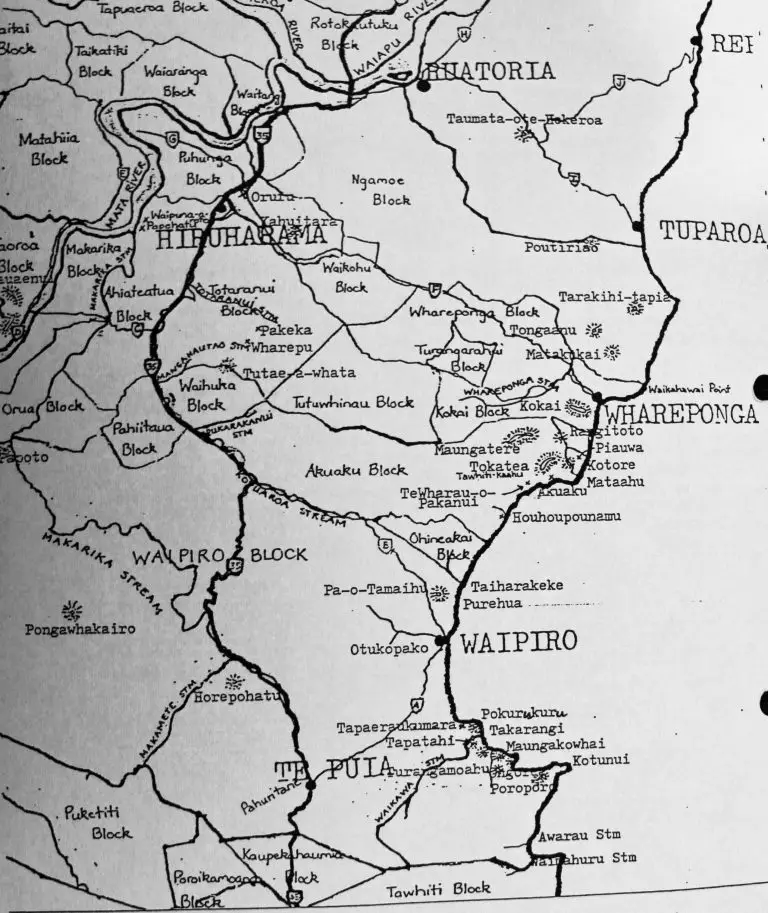

Te Tairawhiti Rohe o Ngāti Porou

“MAI I POTIKI RUA KI TE TOKA-A-TAIAU”

Landmarks etc Waipiro Bay from South to North

• Tawhiti Maunga

• Koutunui Head

• Waiwhero (Orange Bay); Ongore (where we used to gather kaimoana as children); Waikawa.

• Te Rorohukatai – the beach where the Waikawa Stream enters the bay (named after one of the great battles fought here).

PA SITES: Poroporo, Turangamoahu, Maungakowhai, Tapatahi, Takarangi, Pokurukuru, Tapaeraukumara.

The Boat Shed

Purehua (the site of the present village of Waipiro); Te Pa-o-Tamaihu.

Taiharakeke, Houhoupounamu, Akuaku, Mataahu.

PA SITES near Whareponga: Tokatea; Piauwa; Rangitoto; Maungatere; Kokai; Tongaanu;

Whareponga.

Te Ao Pohatu: The Ancient World

In order to fully appreciate how we came to be who we are, it is necessary to take a look back into the distant past many hundreds of years ago. Oral tradition tells us that the ancient world of our people was characterised by ongoing conflict, constant battles, seeking utu (vengeance), and the quest for power. Much of what now follows depicts the movements of these people to relocate in different localities and the subsequent battles that were fought, finally culminating in our tipuna, Iritekura, settling in Waipiro Bay. It may be a beautiful and picturesque bay now but that was not always the case in the past when raging battles and much slaughter took place right here. This idyllic part of the Coast was once densely populated by Ngati Ruanuku , Ngai Tangihaere, and Te Wahine Iti. (Our other tipuna, Ruataupare, wife of Tuwhakairiora, established herself in Tokomaru Bay, but as I have already pointed out, I will leave that story to be told by someone else).

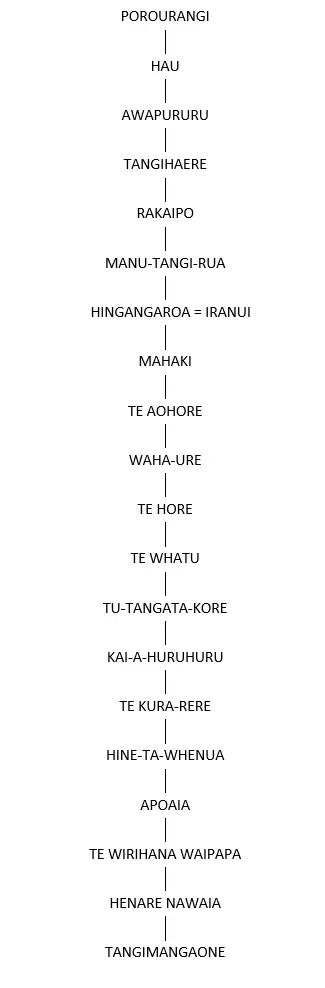

Let us begin this look at the past with a brief examination of the whakapapa that stems from our eponymous ancestor, Porourangi.

Porourangi

|

Hau

|

Awapururu

|

Tangihaere

|

Poroumata

|

Te Atakura

|

Tuwhakairiora

Porourangi —— Hamo-te-rangi ——— Tahu-potiki

|

Ruanuku

Porourangi lived principally at Whangara. His brother was Tahu-potiki. Tahu ventured south and settled at Kaikoura in the South Island.

Porourangi fathered three children (see below)

Porourangi

|

|— Ueroa

|— Rongomaianiwaniwa

|— Hau

|

Rakaipo

He Uri Na Porourangi

Hau married two sisters, Takotowaimua and Tamateatoia. Takotowaimua, his senior wife, soon became pregnant, but during her pregnancy she became fond of her husband’s younger brother, Ueroa. Hau discovered this and the two brothers quarrelled furiously. The brothers could no longer live in the same place, so Ueroa decided to leave Whangara, taking with him his brother’s wife. The parting of the two brothers is known as Te Taranga i a Ue raua ko Hau, the Parting of Ue and Hau and is commemorated in two prominent peaks at Te Mawhai, south of Tokomaru Bay called Ue and Hau.

At the height of the quarrel the brothers threatened to take arms against each other. Hau made himself ready at night for the combat. Later Hau was to name his eldest son Rakaipo commemorating that night he furnished himself in battle array. But the brothers did not come to arms and Ueroa along with Takotowaimua left the Whangara area.

While grieving for the loss of his senior wife, Hau’s junior wife, Tamateatoia sought to console him, by bidding him:

“Tahuri mai ki au to wahine iti”

(“Turn to me, your junior wife”).

She won his love and together they had three sons, Rakaipo, Awapururu, and Tuere.

Thus originated the name Wahine-iti. It was by this name that the descendants of Hau and Tamateatoia, the junior wife, were to become known. In time these Wahine-iti migrated northwards from Whangara and settled in the Waiapu Valley along the southern side of the Waiapu River.

Ngāti Ruanuku

Prior to the migration of Te Wahine-iti, Porourangi died. News of his death reached Tahu in the South Island and Tahu returned to mourn for his elder brother.

Tahu brought with him a group of slaves. After the tangi, Tahu took his brother’s widow to wife. She became pregnant and gave birth to a son whom they named Ruanuku.

After a while Tahu decided to return home and he left the slaves as servants for his young son, Ruanuku. When Ruanuku grew up he went to live with his father in the South Island.

He left behind his servants and they grew in number carrying the name of their master. They became known as Ngati Ruanuku. After a period of time they left Whangara and settled in the Whareponga area.

Ngai Tangihaere

Tangihaere, who was Hau’s grandson moved from Whangara and settled for a while at Uawa. There he

married his cousin, Rakaimoehau. They had many children. Tangihaere and his family then ventured north to Whareponga. There he laid claim to large sections of land that had belonged to his forefathers. On this land Ngati Ruanuku had also settled and they remained in peaceful occupation with Tangihaere and his family. Their neighbours (south of them at Waikawa) were a section of Wahine-iti. And so it was among Ngati Ruanuku and Te Wahine-iti that Tangihaere’s family came to live.

Poroumata

Poroumata, the eldest of Tangihaere’s sons, was the most influential and he was treated with all the respect that goes with the honour of being a chief. And his brothers too were treated in the same way. Poroumata married his cousin, Whaene, who was a chieftainess of Te Wahine-iti.

It is the early 1500’s. Poroumata and his brothers are living at Whareponga; Ngati Ruanuku are living among them; Te Wahine-iti are close by and the more ancient settlers, Ngati Ira are further inland. It was about now that one of the most influential events in the history of Ngati Porou was about to unfold.

Poroumata and his wife, Whaene have six sons and three daughters:

Poroumata —— Whaene

|

|– Taratu (m)

|– Tararere (m)

|– Tarapaoa (m)

|– Taraongaonga (m)

|– Tarauerereao (m)

|– Taratahamoana (m)

|– Materoa (f)

|– Tawhipare (f)

|– Te Ataakura (f)

The slaying of Poroumata and his sons

The fishing catch for the day was landed at Whareponga and the fishermen were setting aside portions for Poroumata and his family as they had always done. As usual the attendants from Poroumata’s pa could be seen making their way down to the beach. However, as the attendants drew closer, the fishermen noticed that Poroumata’s sons were among them.

The fish are apportioned out in kits and on mats. The villagers gather to await their share. Poroumata and his sons are always allotted the biggest share and the best of the hapuka. But this does not satisfy Poroumata’s sons who help themselves to fish set aside for others.

Not only are the locals disgusted by this behaviour; they are also incensed by the liberties that Poroumata’s sons take with their womenfolk each night. They discuss what they might do about the situation. Finally, a plan is approved.

They would build a new ponga house for Porouata (This is how Whareponga got its name). The day before the opening of the new house, Poroumata and his sons would be invited to go out fishing with the local Ngati Ruanuku. Once out at the fishing grounds a signal would be given whereupon Poroumata and his sons would be disposed of.

On the chosen day, when the canoes were about to put to sea, Poroumata and his sons were invited to travel in separate vessels. Once they had reached the fishing ground, they started baiting their hooks. Un-noticed the men in the different canoes winked to each other signalling that it was time to kill Poroumata and his sons. The slaughter commenced. All were killed. The fishing ground where this event took place is known as Kamokamo (winking). Poroumata’s insides were ripped out and thrown into the sea. They were washed up at the mouth of the Whareponga stream, and this place is still known as Tawekatanga-o-te-ngakau-o-Poroumata (The place where the entrails of Poroumata lay entangled).

Of Poroumata’s sons, only Taratahamoana survived. He was living with his uncle Haukotore at Matakukai when the murder occurred. He was allowed to live after the murder of his father and brothers as he, like his uncle, was probably of no threat to the many Ngati Ruanuku. Tahamoana grew up in Whareponga.

Ngati Ruanuku would not have known that their killing of Poroumata and his sons would lead eventually to their extermination as a tribe. That story is yet to unfold in the form of two of Poroumata’s grandsons, Tuwhakairiora and Pakaanui.

What of Poroumata's three daughters:

Materoa, Tāwhipare & Te Ataakura?

Materoa

Materoa was living at Poutiriao Pa, inland from Tuparoa. There she was seduced by her cousin, Rangitarewa who noticed how beautiful she was. They spent one night together which resulted in her becoming pregnant. Distressed at what had happened, Materoa went to live with her relatives at Pourewa in the Uawa district.

Materoa —— Rangitarewa

|

Tamaihu ——— Hinepare (grand-daughter of Hauiti)

|

Tutehurutea

Tamaihu lived at Purehua, the present site of Waipiro village. His pa was Te Pa-o-Tamaihu. Tamaterongo, a young chief from Turanga, had heard of the beauty of Materoa. With a small band of warriors he set out for Uawa to discover for himself. Upon meeting her and despite her pregnancy to Rangitarewa, Tamaterongo took her back to Turanga.

Hearing that Materoa had given birth to a son and had been moved to a Whare Kohanga, Rangitarewa travelled to Turanga to claim his child. Undetected, he found Materoa alone with their infant son. He took the child from her and then journeyed back to Poutiriao Pa. When Tamaterongo was told what had happened, he set off in pursuit of Rangitarewa and the infant child, but he was too late.

Materoa and Tamaterongo had nine children all of whom were born and brought up at Titirangi Pa.

Materoa ——— Tamaterongo

|

|– Hinetu

|– Rongotehengia

|– Kuraunuhia

|– Kahupakari

|– Pareongaonga

|– Kotaroa

|– Hika

|– Piko

|– Poroungaronoa

Tāwhipare

Tāwhipare, one of Poroumata’s three daughters, holds a significant place in Ngāti Porou whakapapa, though her story is less prominent than that of her sister Materoa. Her lineage and alliances contributed notably to the shaping of iwi relationships and territorial dynamics along the East Coast.

Tāwhipare married Kahukuranui, a descendant of Hauiti, thereby intertwining the lines of Poroumata and Hauiti. This union produced two sons: Tautini and Hurumangiangi. Through Hurumangiangi, the whakapapa extends to Uetuhiao, who married Tūtehurutea, a grandchild of Materoa, Tāwhipare’s sister. This intermarriage between the descendants of Tāwhipare and Materoa further solidified the familial and political bonds within Ngāti Porou.

Tautini, Tāwhipare’s other son, became a prominent figure in the Tokomaru Bay region. He married Rongomaihuatahi, and their lineage continued through their daughter, Te Aotāwarirangi. Tautini’s influence in the region was significant, and his descendants played vital roles in the local power structures.

Te Ataakura

The youngest daughter of Poroumata, Te Ataakura, married Ngatihau and settled at Uawa. After a time they had to leave as Ngatihau and his people had been accused of taking kumara from a neighbouring garden. They travelled to Opotiki where some of Ngatihau’s relatives lived.

Te Ataakura still mourned the death of her father and her brothers. Hers was a mourning for a death unavenged. She longed for revenge so much that when she found she was pregnant with her first child she begged the forces of nature to let that child be a boy so that he might grow to avenge the death of Poroumata and his sons. But it was not to be and she gave birth to a daughter. She named the child Te Aomihia (The cloud that was welcomed) in memory of the clouds which her father welcomed when he put to sea to his death. She conceived a second time but again it was a daughter.

When she conceived a third time the baby in her womb moved about. Upon feeling this movement, Te Ataakura uttered “Ei, kia takatakahi koe I roto I a au, he tane, e ea i a koe te mate o toku papa” “Ah, move thou spiritedly within me, a son, you will be the one to avenge the death of my father”).

|

|– Te Aomihia

|– Whakaarorangi

|– Tuwhakairiora

Tuwhakairiora

As Tuwhakairiora grew he flourished under the guidance of tohunga. He mastered the skills of armed combat. He notched up numerous notable deeds of bravery; he entered the field of battle many times and always returned victorious. His fame as a warrior had spread abroad; he had acquired the emblems of bravery in battle whereby the enemy were overcome.

Here was a rangatira indeed; one who had barely reached manhood yet achieved more than any man his age had ever dreamed And why? Because he was special; he had been dedicated from birth; he had a mission. He was not like the other chiefs, for they knew as he knew that he was destined to a task so daunting that the thought of it stirred the blood within. There had never been one like him nor has there been one since. Tuwhakairiora was a toa rangatira, a supreme warrior champion.

Eventually, the day arrived when Tuwhakairiora set out to avenge the death of his grandfather, Poroumata, and thereby fulfil his mother’s wish. His followers wished to accompany him and participate in the great battle that was to come. But Tuwhakairiora insisted that he travel alone: “Kati, ko au anake e haere. Tena ona iwi hai kawe i a au” (I shall go alone. There will be the tribes connected to my grandfather who will escort me”).

He left Opotiki with his parents and relatives only. They stopped for a while at Te Kaha, then Orete, and then at Whangaparaoa where he left his family and travelled alone to Kawakawa (Te Araroa).

At Okauwharetoa he married Ruataupare and set about establishing himself in the Kawakawa region. This he did by allying himself with the great tribes of the area, and by subduing those who stood against him. His strategy and leadership at this time was unmatched by his peers and as his reputation continued to flourish so did the size of his army.

He was in the prime of his fighting life bringing about the destruction of Ngati Manu, Ngai Tumoana and the Pararaki tribe. He was now ready to travel south to Whareponga and to attack Ngati Ruanuku.

The Battle known as Te Hiku Tawatawa

(The Tail of the Mackerel)

Tuwhakairiora selected a very strong but limited force of warriors and then set sail for Whareponga. Ngati Ruanuku would have been aware of the impending attack against them and had, therefore, assembled in their main pa, Tongaanu, Kokai, and Tokatea. Tuwhakairiora’s warriors made landfall in the early hours of the morning.

News of their arrival spread like wildfire among the many thousands of Ngati Ruanuku. Because Tuwhakairiora’s force appeared to be quite limited in number, Ngati Ruanuku were confident of victory. But what they may have lacked in numbers they made up for in skill, fitness, determination and courage plus the generalship of their great leader.

Tuwhakairiora directed his army into position below Tongaanu Pa.

He organised his men into three attacking forces:

- Puarere, whose job it was to effect an entrance into the pa and set it alight;

- Whare-o-te-riri, the main group made up of warriors of exceptional skill and bravery;

- Patari, a group of warriors who would be used as reserves to back up the main group.

Tuwhakairiora instructed each group as to what they had to do. Meanwhile thousands of Ngati Ruanuku poured out of their pa and assembled on the beach confident that because of their greater numbers they would soon annihilate the enemy. After instructing his warriors, Tuwhakairiora, who was in a state of tapu, calmly said to his kai-whangai,

“Homai te hiku o taku tawatawa, whangaitia mai kia pau”

(“Give me the tail of my mackerel and feed me till it is all gone”)

When he had finished eating the tail of his fish, he stood up and surveyed the situation. Then he gave the order to attack. Although vastly outnumbered, such was the magnificent fighting ability and skill of Tuwhakairiora’s warriors and their utter belief in their leader, that Ngati Ruanauku were soon in disarray. They scattered in all directions fleeing for their lives but they were pursued and killed in their thousands.

The Ngati Ruanuku pa were all destroyed by fire. For many days the slaughter continued. News was sent back to Te Aotaki (Ruataupare’s father) at Okauwharetoa that Ngati Ruanuku were no more.

Tuwhakairiora’s mission had been accomplished. He then returned to Okauwharetoa.

Pakanui

Materoa ——— Tamaterongo

|

Rongotehengia —— Hinetauperangi

|

|– Pakanui

|– Rongopakihiwi

|– Rongotaumangi

|– Rikipapaki

|– Tuteuruhina

|– Rarotaka

|– Raroapohia

|– Hikaraupi

Let us return to Pakanui, Materoa’s grandson.

Tutehurutea carried news of Tuwhakairiora’s slaughter of Ngati Ruanuku to his grandmother, Materoa, at Titirangi Pa. When he had finished his report Materoa said: “Kua ea te wahanga ki taku taina. Engari, ko te wahi ki a au kei te toe. Ma wai e ngaki te wahanga ki a au? Ma taku mokopuna, ma Pakanui, Tikina mai a Pakanui”. (“My sister’s grief for the deaths of our father and brothers has been appeased. Mine has not. Who is there that can end the pain within me? There is none other than my grandson, Pakanui. Send for him”).

Pakanui had built a reputation as a great fighter in the many battles he had fought in the Turanga district. In fact, at the time that Materoa asked for him he was away fighting yet another battle against Ngati Kahungunu at Nukutaurua, Whakaki, and Te Wairoa. When Tutehurutea found Pakanui he gave him news of Tuwhakairiora’s conquest and of his grandmother’s request. Pakanui was envious that he had not

conquered Ngati Ruanuku himself. He returned to Titirangi Pa where he rested his troops before proceeding up the coast to Whareponga.

Pakanui further avenges the deaths of his grandfather and his uncles

Without going into too much detail, let us simply say that Pakanui, with a limited number of warriors, was able to completely exterminate any remnants of Ngati Ruanuku. Following the Battle of Te Ika Koraparua, the Battle of Taitimuroa, and the Fall of Kahuitara, Ngati Ruanuku as a tribe ceased to exist. Poroumata’s murder had been fully avenged first by Tuwhakairiora and then by Pakanui.

The Battle of Te Rorohukatai

With the fighting over and Ngati Ruanuku disposed of, Pakanui decided to send most of his men home. Only sixty of them remained and these men along with his brothers moved with Pakanui down the beach to Waikawa.

Pakanui built a pa along a ridge called Pokurukuru. Right alongside him lived the Wahine-Iti in their numerous pa, Tapatahi, Takarangi, Maungakowhai, and Turangamoahu. Pakanui resided for a long period of time among the Wahine-Iti who had little time for him because of his annihilation of their neighbours, Ngati Ruanuku.

After enduring many taunts and insults Pakanui’ with his small numbers of warriors, made some attempts at dealing to these Wahine-Iti but he soon realised that he was in no position to overcome them with his small contingent. He then sought the assistance of his uncle, Tuwhakairiora, who with his sons and a fighting force soon travelled south to Waipiro Bay.

On reaching Mataahu they put ashore. It was dark at this time and the Wahine-Iti were unaware of their arrival. Quietly Tuwhakairiora’s army made its way down the beach to Tapaeraukumara where they camped. Tuwhakairiora sent for Pakanui who came down from Pokurukuru to meet his uncle. There on the beach they laid their plan.

Pakanui was to attack one of the Wahine-Iti pa, retreat, and try to draw the enemy towards Pokurukuru. Once they crossed the Waikawa Stream, Tuwhakairiora, who would be hidden with his freshly rested troops, would charge from around Pokurukuru Point. With this advantage Tuwhakairiora and Pakanui hoped to win the battle.

The next morning the Wahine-iti awoke still unaware of the presence of Tuwhakairiora, as Pokurukuru Point kept his camp out of sight. Pakanui and his men moved towards Takarangi Pa. The Wahine-Iti rushed out to do battle with Pakanui comfortable in the knowledge that they could easily overcome them. Pakanui and his men retreated. All the warriors fom the Wahine-Iti Pa, Te Poroporo, Maungakowhai, Turangamoahu, Ongore, and Tapatahi were soon emptied.

Quickly Pakanui and his men retreated across the Waikawa Stream with hundreds of Wahine-Iti in hot pursuit. Tuwhakairiora then ordered his men to charge. They burst out from Pokurukuru Point into the face of the oncoming enemy. Utter confusion arose among the Wahine-Iti at this change of circumstance Tuwhakairiora, along with his sons and battle-hardened troops and with Pakanui were relentless in their attack against Te Wahine-Iti who lost all of their chiefs and hundreds of their followers.

As Pakanui, Tuwhakairiora, and their troops regrouped and made their way back to Takirau they passed the bodies of those killed. These lay strewn all along the beach from Ongore to Takirau. As the waves broke and washed ashore the froth mixed with the spilled brains of the many dead. That is how the name of this battle, Te Roro-Huka-Tai, arose (The brains mixed with the froth of the tide).

With the battle over and the Wahine-Iti cleared out of the Waipiro district completely, Tuwhakairiora returned to Okauwharetoa while Pakanui remained in Waipiro.

Iritekura

Te Ataakura

|

|– Whakaarorangi

|– Tuwhakairiora

|– Te Aomihia

|

Iritekura ——— Ruatona

"Ina nga pungarehu a ou tungane"

"Here are the ashes of your cousins"

After the battle of Te Roro-huka-tai, Pakanui shifted into Tapatahi Pa. There he cultivated a kumara garden, Peke-a-te-akau. Living in the vicinity were the Ngati Whakapuke, a section of the Wahine-Iti whom Pakanui had allowed to remain in a position similar to slaves.

Meanwhile Tuwhakairiora had taken up residence once again at Okauwharetoa. With him had come to live his niece, Iritekura. She had come with her husband Ruatona and their children. Iritekura asked her uncle for some land whereby they could grow kumara. Tuwhakairiora’s response was:

“Kaore he kainga hai hoatutanga maku ki a koe. Kati, haramai, haere ki runga ki ta matou pungarehu ko au tungane noho ai”.

(“I have no place to give you here. But come, go to the battleground of myself and your cousins and reside there”).

By so speaking Tuwhakairiora was gifting the Wahine-Iti lands at Te Rorohukatai to his niece. Iritekura of course was overjoyed and eagerly prepared to depart. She arrived at Waipiro with her family and people and set up camp on the southern bank of the Waipiro Stream.

When Iritekura visited Pakanui at Tapatahi pa he asked her:

“He aha to tira?”

(“What have your people come for?”).

Iritekura replied:

“Na Tuwhakairiora au i tono mai ki runga ki ta koutou pungarehu ko o taina”.

(“I have been sent by Tuwhakairiora onto the battleground of yourself and your brothers”).

Pakanui showed her what was once the Wahine-Iti land and repeated the gift:

“E tika ana, ina nga pungarehu a ou tungane”.

(“You are right in coming. Here are the ashes of your cousins”).

Pakanui then showed Iritekura the land that was now hers. Pakanui showed her his maara, Peke-a-te-akau, and told her it was now hers. He took her to his rua kumara and made the kumara over to her as well.

Finally, he gave her the Ngati Whakapuke people as servants to work her cultivations. Once Iritekura and her people had settled in at Tapatahi, Pakanui moved out and after a little while he and his troops moved back to Turanga.

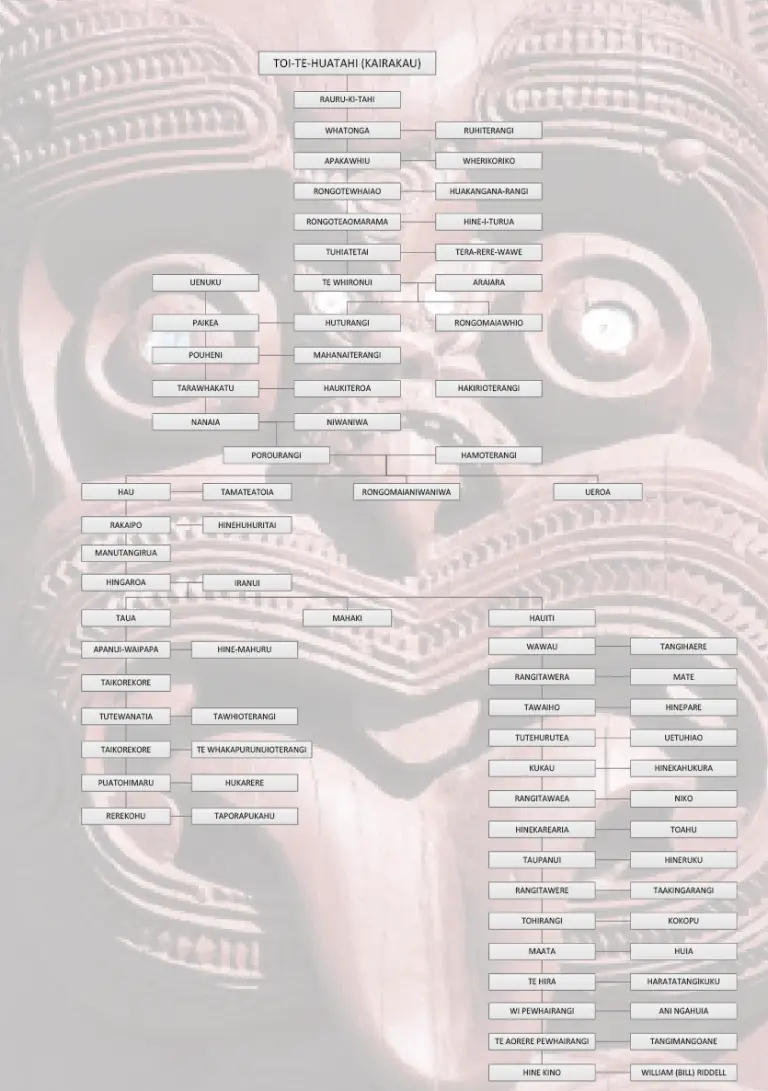

Whakapapa chart from Toi-Kai-Rakau

Te Whānau-a-Ruataupare

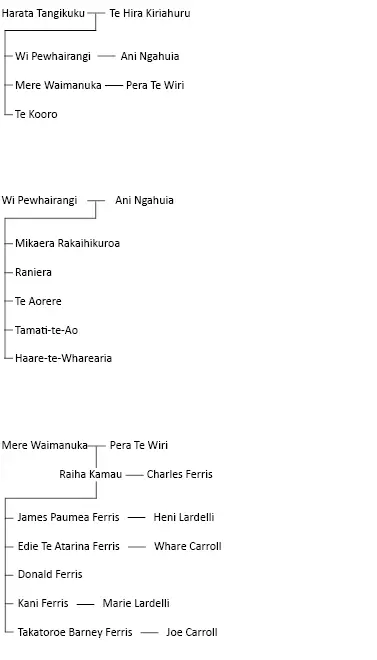

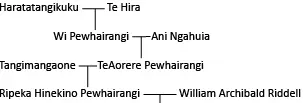

Taha ki te whānau PEWHAIRANGI

Te Whānau-a-Iritekura

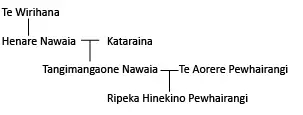

Taha ki te whānau NAWAIA

Henare Nawaia and Kataraina had five daughters:

• Tangingahooro (The Henare, the Hikitapua, the Northover and the Ruwhiu families)

• Tangimangaone (The Pewhairangi, the Matahiki and the Riddell families)

• Pareake (The Tuhaka family)

• Ngarere (The Pokai and Bartlett families)

• Tangiwai (The Tapiata family)

Let us return to the Harata Tangikuku and her whānau

Tangimangaone Nawaia

Pewhairangi, Matahiki & Riddell whānau

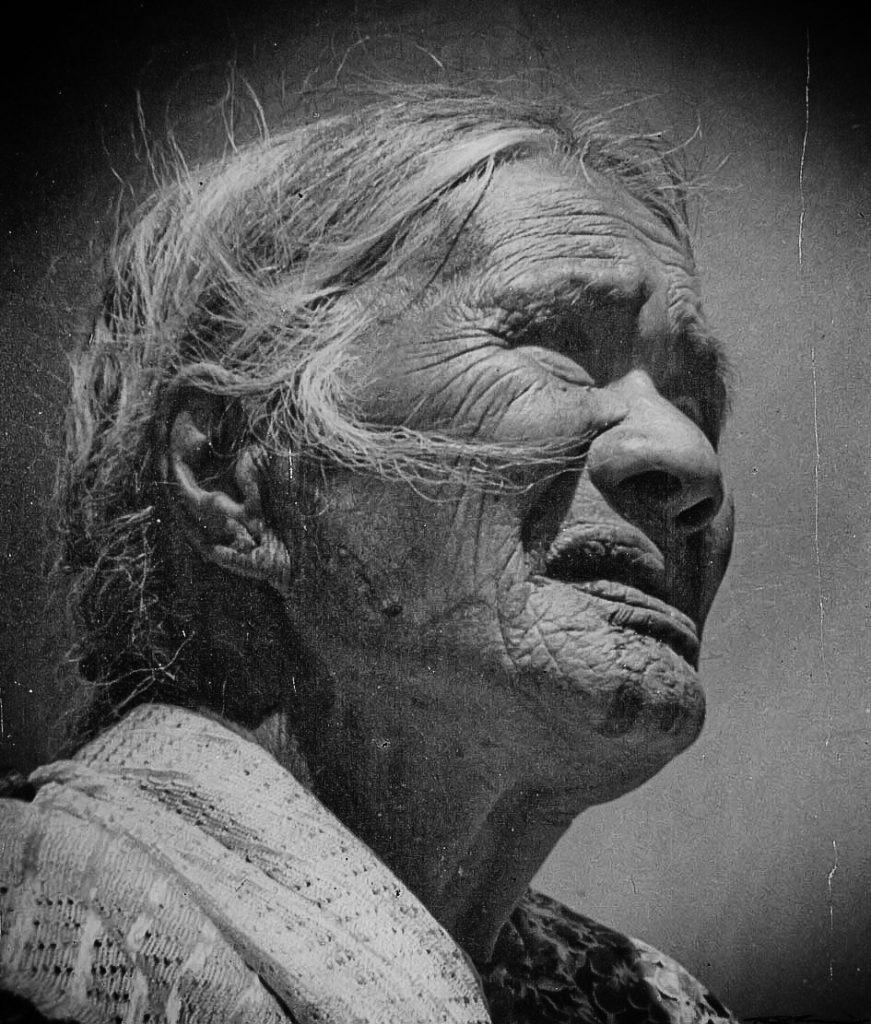

She died in her nineties in 1956 and lies buried here in Waipiro, with her daughter, Ripeka Hinekino, our mother, beside her.

Some of us were fortunate to have known and lived with a grandmother from another age, Tangimangaone was a very learned woman. She was a tohunga (expert) of the old order, steeped in the knowledge of her world: of whakapapa, karakia, waiata, rongoa (medicine), raranga (weaving), te ngahere (the forest), te moana (the sea), matauranga Maori.

She was a matakite (a seer; one who could foresee the future) and she could cure illnesses with the power of prayer. She was a deeply spiritual person and a firm believer in the teachings of Te Kooti Rikirangi. As a staunch Ringatu she would chant her karakia and waiata every night.

Because of her exceptional ability in the retention of knowledge, she was often consulted by other elders of Ngati Porou about historical events, whakapapa, waiata and so on, She was a fountain of knowledge. In order to maintain her power of retention of memory, she would only wash her head in either cold water or in water that had been warmed by the sun; never in water that had been warmed over a fire.

Such was her appreciation and understanding of the value of education, that she sent some of her children away to boarding school. For example, Kirikiri went to Hukarere, Tutaawa to Te Aute College, Hinekino to Queen Victoria School and later to Saint Joseph’s Maori Girls’ College, and Haare to St Stephen’s.

Remember, this was in the early part of the 20th century about 100 years ago. Tangimangaone and her husband, Te Aorere Pewhairangi were married on the 9th March 1883 and on April 23rd 1883. Wi Pewhairangi, Te Aorere’s father, records their “moe” and “marena” in his own writing as follows:

“Maehe 9 1883. No tenei marama i moea a Te Aorere i a Mangaone”.

Aperira 23 1883. No tenei marama i marenatia ai raua. No te 23 o nga ra o tenei marama i honoa ai ki ta te Atua ritenga”.

They lived on her land , Puke Taahuna, in Te Puia. Te Aorere had a small dairy herd that he milked by hand (the cream was sent to the dairy factory in Ruatoria), some sheep, some beef cattle, and a large maara or mahinga kai (vegetable garden). Although the farm today is covered in manuka and blackberry, in Te Aorere’s time it was in pasture apart from the native bush that runs down the middle of the land.

Tangimangaone spent much of her time living at her various marae, Waiparapara, Taharora, Te Kiekie, and Whareponga. She also had two “retreats” on her land to which she would retire during the summer months. Much of her time at these “retreats” would be spent in quiet meditation and prayer. As children we used to enjoy spending time with her in these camps eating her paraoa kororirori, paraoa takakau, paraoa parai, miiti tahu, and dried mango. We couldn’t speak her language and she did not speak English but we understood one another.

On certain days of the month, especially on the 1st and the 12th she would put some coins into a saucer on the table and bless them while having a meal. She would then bury them at the base of an old ngaio tree or throw them into the creek below the well.

As an old lady she was very fit, often walking the 5 miles or so between Te Puia and Taharora in Waipiro. She was well into her nineties when she died, Initially, her body was taken to Te Ariuru Marae in Waima, and then to Pakirikiri Marae in Tokomaru. Knowing that she didn’t belong there, Tawhai Tamepo secreted her body away on his truck in the middle of the night and took her to Iritekura Marae in Waipiro Bay where the appropriate rituals were conducted. She lies buried in the Waipiro Bay cemetery being one of the last to be buried in the old cemetery.

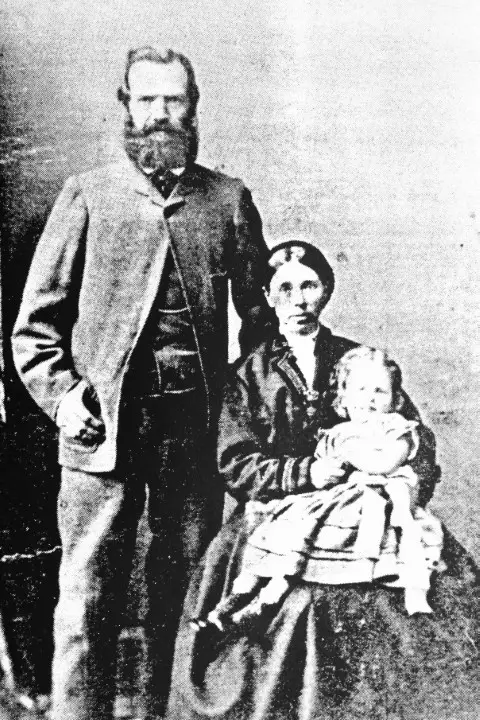

Ripeka Hinekino Pewhairangi

Ripeka Hinekino Pewhairangi, also known as Ripeka Hinekino Riddell, was born in 1903 in Tokomaru Bay. She was the daughter of Te Aorere Pewhairangi and Tangi Mangaone Nawaia.

Her father, Te Aorere, was born around 1870 in Tipaka, East Coast, and passed away in 1930. Her mother, Tangimangaone Nawaia, was born in 1866 and died in 1956.

Ripeka married William Archibald Riddell, and together they had 14 children. She passed away in 1960 at the age of 57.

Our Scottish whakapapa

Who were out Scottish ancestors?

John Riddell

| Margaret Turnbull b.1777

|– James Riddell 1804-1892

James Riddell 1804-1892

| Jane Goodall 1805-1869

|– John 1828-1902

|– Andrew 1829-1895

|– James 1831-1919

|– Janet 1833

|– Walter 1835-1914

|– Margaret 1841

|– Robert 1838-1924

|– Margaret 1841

|– William 1842-1850

|– Patrick 1845-1902

|– Jane 1847

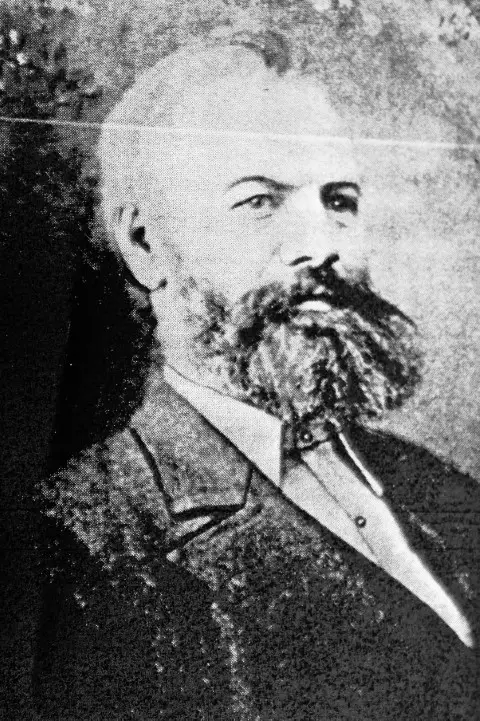

Andrew Riddell 1829-1895

| Janet Arndel (Arundel) 1827-1900

|– James 1856-1932

|– Thomas 1858-1947

|– Ann 1860-1937

|– Andrew 1866-1910

|– John 1866-1936

|– Jane 1868-1947

John (Jack) Riddell 1866-1936

| Maggie McQuilkan 1875-1926

|– John 1898-1968

|– Margaret 1900

|– James 1901-1973

|– William (Bill/Billy) 1902-1986

|– Catherine 1904-1990

|– Effie 1906

Where were they from, and what did they do?

“Ancient Riddel’s fair domain

Where Aill from mountain freed

Down from the lakes did raging come”.

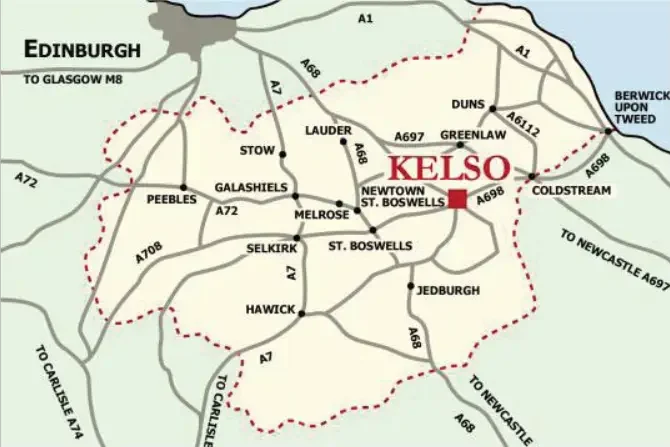

These words by Sir Walter Scott place Riddell country deep in the heart of the lovely Border area of Scotland.

The Ale as it is now known is a tributary of the river Teviot, which in turn flows into the Tweed at Kelso.

A few miles to the west is the estate of Riddell close to the village of Lilliesleaf and again further to the south, the tiny hamlet of Hobkirk and the Wauchope forest situated between Hawick and the border with England, both a part of our Riddell origins.

They came from the southern part of Scotland known as The Borders. The towns and villages where they lived and worked were Hawick, Kelso, Lilliesleaf, Hobkirk, Wauchope, Stitchil, Sprouston, Abbotsford and Nenthorn. Most of our male ancestors worked the land generally as shepherds.

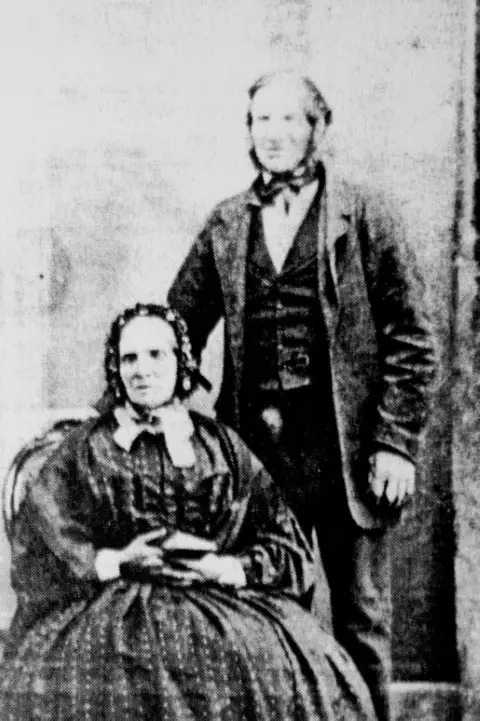

John Riddell & Margaret Turnball

Let us start with JOHN RIDDELL who married MARGARET TURNBULL. John was born in Hobkirk and was a shepherd on the Wauchope estate.

John and Margaret had nine children who were all born at Wauchope. Later the family moved to Clarilaw (near Lilliesleaf) where John was a shepherd for many years. They later moved to a farm called Berryhill (close to Abbotsford). John became a small landowner with initially 20 acres, he later owned 38 acres.

John and Margaret and members of their family are buried in the Bowden churchyard.

James Riddell & Jane Goodall

James was the third child of John and Margaret. He was born in 1804 and like his father, became a shepherd. He married Jane Goodall in 1827. They lived in the Kelso area working on farms at Stitchel and Sprouston and finally at Girrick, all a short distance from Kelso.

They had eleven children but two died while young. Of these, six brothers migrated to New Zealand with the view of forging a new and better life for themselves. A sister went to Canada. Jane died of pneumonia in 1869 at the age of 64. James died in 1892 at the age of 87. James and Jane with their two children are buried in the Old Nenthorn Cemetery.

It must have been heart-wrenching for James and Jane knowing that as their six sons and one daughter left them to establish themselves on the other side of the world that they would not see them again.

This verse from Robert Burns’ poem, The Farewell, expresses how they must have felt on lonely nights:

When day is gane, and night is come,

And a’ folks bound to sleep;

I think on him that’s far awa’,

The lee-lang night, and weep,

My dear,

The lee-lang night, and weep.

Andrew Riddell & Janet Arndel (Arundel)

Andrew was born in 1829. He married Janet Arndel (Arundel) in 1856.; he was 27, his wife was 29.

Their first three children were born in Scotland – James (1856),

Thomas (1858), and Ann (1860).

They arrived in New Zealand in 1862. Andrew brought the first flock of Leicester sheep to North Otago; arrived at Port Chalmers on the ship Simoon early January 1862 with 1000 Leicester sheep (lost only 5% of the flock; an outstanding accomplishment when one considers the small ship they travelled in and being at sea for 77 days).

1863 saw the birth of their fourth child, Andrew. He worked on the Kauru run as a shepherd. The family moved to Southland in 1866 when JOHN was born. He was born at Longbush, not far from Woodlands in the Waikato.

Their last child, Jane Janet was born in 1868. By this time the family was living in Morton Mains. Andrew worked for the New Zealand and Australia Land Company.

Four of the Riddell brothers were living in Southland around this time – Andrew, Robert, Walter and John. Andrew managed Moeraki Station near Hampden, 20 miles south of Oamaru. Here, the elder daughter, Ann, married Samuel Caque. Andrew was also appointed to the Moeraki Harbour Board in 1877.

Andrew and Janet retired to Oamaru. He died there in 1895 when he was 65 years old and is buried there.

Janet spent the rest of her life with her daughter Jane (“Ginny”) and her husband, Jack Johnston in Herbert. She died in 1900 at the age of 73 and is buried beside her husband in Oamaru.

Andrew’s and Janet’s four sons were all living in the North Island.

Their children in adult life

James

James was 5 years old when the family migrated to New Zealand He also became a shepherd; worked mainly in Central Hawkek’s Bay; managed a sheep station near Waipawa; died in Waipukurau Hospital in 1932; buried in Waipawa; 75 years old.

Thomas (Tom)

Thomas was 3 or 4 years old when his family arrived in New Zealand; also became a shepherd; moved to the Waikato; worked near Cambridge. Married Isobella McFarland in Cambridge in 1884.

Moved back to the South Island where he worked as a shepherd at Lake Sumner in North Canterbury.

Moved back to the North Island and was a stock agent in Eketahuna and Pahiatua. Thomas became a butcher till he retired to Masterton where he died in his 90th year. Had 6 children.

Ann

Ann was an infant when the family came to New Zealand. Married Samuel Caque in 1879.

Widowed after 17 years of marriage. Samuel died of cancer in 1896 leaving his wife and 7 children.

Ann lived her life in South Canterbury. She died in 1937 in Timaru at the age of 77. She is buried next to her husband in the Otaio cemetery.

Andrew

Andrew was their fourth child, the first to be born in New Zealand Born at the Kauru run in 1863. In 1890 he was a shepherd at Shag Vallet Station near Palmerston South. From 1894 to

1900 he worked as a shepherd in Takapau, Hawke’s Bay.

He married at the age of 30 then moved to Wellington with his wife and four children. They lived in Petone. He worked for a bacon factory as an engine driver. Died in 1910 after falling from a platform onto a concrete floor.

Andrew is Joan Bolger’s grandfather. (Joan Bolger is the wife of past prime minister of New Zealand, Jim Bolger).

Our immediate whakapapa

Grandparents

1902-1986

Ripeka Hinekino Pewhairangi

1903-1960

Children

Iritana (Iri)

1925-

Heather

1926-1996

Maud

1928-2009

Robin

1930-1982

James (Jim)

1931-1989

Michael (Mick)

1932-1997

Wilma

1935-2008

Aorere (Awi)

1936-2024

John

1939-2015

Valerie (Val)

1940-1999

Massey

1942-2011

David

1943-1982

Basil

1945-

Frank

1947-

Grandparents

William (Bill/Billy) Riddell 1902-1986

| Tahua Gomez (nee Honatana) 1934-1999

|– Wilma

|– Robin 1959-

|– Debbie 1962-

William (Bill/Billy) Riddell 1902-1986

| Georgina Ngarimu

|– Josephine Mokomoko